Cotton Origin Focus: China - Part 1

- Diego Miranda

- Aug 26, 2025

- 7 min read

Updated: Oct 14, 2025

China Cotton Sector At-a-Glance

Production: ~31 million bales annually (average last 5 years).

Leading Region: Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (~90–95% of national output); minor production regions include Yellow-Huai (Hebei, Henan, Shandong) and Yangtze (Jiangsu, Hubei, Anhui) river areas.

Cotton Type: Primarily Upland cotton; Xinjiang produces significant volumes of premium Extra-Long Staple (ELS) cotton.

Farm Structure: Xinjiang dominated by large-scale mechanized farms (including state-run XPCC). Elsewhere cotton is produced mostly on small family farms (~0.5 hectares).

Harvesting Method: Xinjiang (~80–90% mechanized); elsewhere predominantly manual harvesting.

Why China Matters

Among all the world, it can be said that China holds a central position in the cotton market. The country is responsible for producing approximately one-quarter of the global crop and consuming even more, roughly one-third.

Despite its immense production, China’s hunger for cotton is such that it cannot be satiated by internal supply alone. As such, besides being the biggest producer and consumer, the Asian nation is also the largest importer, buying almost 10 million bales from other countries on average every year.

Given its dual role as producer and consumer, it is no surprise that China possesses significant influence over international prices, global supply chains, and market dynamics. China's policies, such as domestic subsidies, target-price schemes, and extensive state cotton reserves, make it a global price setter. Additionally, the cotton import quotas—set under WTO agreements—greatly affect global trade volumes, driving fluctuations in international markets.

[Stay ahead in cotton markets. Our Premium Cotton Research delivers timely insights and data-driven analysis.]

Of course, China does not plant and buy all that cotton just to sit idly on it. Instead, it is the world’s largest textile producer, accounting for more than half of global cotton yarn spinning capacity. Therefore, the global cotton market is deeply affected by the Chinese economy, since any fluctuation in it is certain to impact the demand companies would have for the commodity.

Taking all this into consideration, it is no surprise that understanding China is an essential aspect for anyone who wishes to be a cotton expert. To know how Chinese history is intertwined with cotton, or better yet, how cotton is intertwined with Chinese history, can provide analysts and traders with deeper insight into cotton market dynamics, helping them predict future developments and make decisions.

History of Production Although not a native plant, cotton has a far-reaching history in China (which we will explore further in coming blogs). Brought from India in 200 BC to the southern provinces, the Chinese cotton sector took centuries to develop, facing innumerable challenges, such as the resistance of the silk industry, the lack of spinning technology, and many different wars, which more than once devastated the fields.

Throughout all this, the cotton sector continued to grow and change, moving from its original producing sites in the South to the Yangzi heartland (Central China), and then to other central and previously unexplored northern regions.

[Get a FREE trial of our premium cotton market research]

As the 19th century was closing, the cotton industry was fairly spread across the country. Although Yangzi still represented 60% of the total crop, other central and northern regions also played a meaningful role in production. Mechanical spinning had also started to develop, supported by British investments and technology, and even though it only represented around 10% of the total spinning in the country, its use was growing at a considerably fast pace.

During this time, China already was an important player in the global cotton markets, producing over 400,000 bales yearly. That said, it was still substantially behind dominant producers such as the United States, which consistently produced over 13 million bales annually, and India, whose production hovered around 7.5 million bales per year by mid-century.

The 20th Century Begins

Production increased further in the coming years, amid the tumultuous period marked by the collapse of the Qing dynasty, the Warlord Era (1916–1928), and the Sino-Japanese conflicts. By the 1920s, total cotton output increased notably to approximately 4 million bales annually, and mechanized spinning expanded substantially, reaching 3 million spindles.

However, the industry's upward trajectory was severely disrupted by the Japanese invasion and occupation (1937–1945). The Sino-Japanese War decimated production capabilities, particularly in eastern provinces where fighting was concentrated. Cotton production plummeted to approximately 2.3 million bales annually by 1940. The war also triggered significant shifts in cotton-growing regions, pushing production further inland, particularly toward provinces such as Henan and Shandong.

[Supply, demand, weather...our Cotton Research covers it all so you can stay informed.]

Post-war recovery was slow and uneven. By 1950, cotton production rebounded modestly to around 2 million bales per year, yet spinning capacity remained below pre-war levels due to the destruction of industrial infrastructure and persistent political instability. The ongoing Chinese Civil War (1946–1949) hindered recovery efforts, and inflation eroded investment incentives, stalling significant growth in the textile sector.

The Communist Revolution The year 1949 decreed the end of internal conflict and the victory of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and the transformation of China into a “People’s Republic”. Following that, the new government started a planned push to modernize and expand cotton production, treating cotton as a key to industrialization – essential for producing textiles, earning foreign exchange, and accumulating capital for development.

Seeing it as a strategic crop, the state quickly brought the entire cotton supply chain under central control. By 1954, all cotton yarn and cloth, whether produced by private weavers or state mills, had to be sold to the government’s Cotton, Yarn, and Cloth Company, which managed distribution under a planned quota system. This unified procurement ensured the state could direct cotton where it wished (primarily to urban textile mills) at controlled prices.

Even by the 1950s, China’s cotton spinning was still dominated by handloom industries and handmade cloth, which managed to resist even the introduction of mechanized competition. Instead of a reason to celebrate, though, the Chinese government saw this as a concern, since it believed the use of old practices would stall the country’s growing cotton industry. For this, the authorities focused many of their resources on guaranteeing that the cotton produced by farmers would go to urban mills and factories.

[Serious about cotton? Our Premium Reports deliver consistent, reliable market intelligence every week.]

Such policies proved effective in boosting output – at least initially. Farmers were instructed in improved cultivation techniques (the first adoption of scientific methods on a large scale) and sown area increased. As a result, cotton production rose rapidly during the 1950s, surpassing 8 million bales. China, traditionally a net cotton importer, became a net exporter of cotton by the mid-1950s. That said, this was achieved by diverting cotton from rural households (who had to make do with less cloth) to state-controlled exports and mill use.

Shock of Reality

This initial increase in production did not last, though. The Great Leap Forward (1958–1961) and subsequent famine forced a focus back on food grains at the expense of cash crops, reducing land and other resources that could be spent on cotton. As a result, cotton production declined sharply at the beginning of the 1960s and was only able to recover in the 1970s.

Even though supply rose in the 1970s, reaching up to 11.4 million bales in 1974, the pace was not enough to match China’s growing population, leading the country to increase its imports substantially compared to the 1950s. At the same time, yields stopped growing, stabilizing around 2,000 bales per ha. This meant that all increases in production needed to be done through the use of more land, which was a scarce resource amid the severe economic conditions experienced in communist China during the period.

At this point, it was clear the current model was unsustainable, and something needed to be done. Fortunately, though, the time of change was coming for all of China, and cotton would not be left behind.

Reform and Expansion

Following the economic reforms of 1978, China’s cotton sector experienced significant expansion and modernization. Market-oriented policies and the household responsibility system, which shifted agricultural production from collective farming to individual households, gave farmers more incentive to increase output.

New farming techniques were also developed, and those created during the 1950s, previously restricted to some small areas, spread throughout the country. The most important change was the cultivation strategy known as “short-dense-early,” which involved compact plant types, denser planting, and early sowing to maximize yield and minimize risks associated with adverse weather conditions.

[Whether you’re trading, hedging, or sourcing—our Cotton Research helps you stay on top of market shifts.]

The results were dramatic: cotton yields grew about 3–4% annually for decades and production skyrocketed, going from 10 million bales on average in the 1970s to over 20 million in the 1990s. The growing crop allowed China to surpass both the US and India, becoming the world’s leading producer.

Voracious Consumer

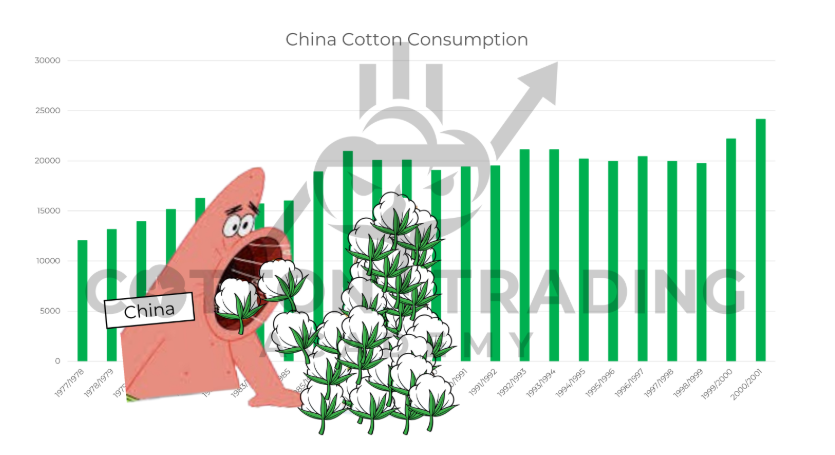

On the demand side, China’s economic boom and the liberalization of its textile industry led to soaring cotton consumption. As export-focused garment factories flourished in the 1990s, domestic cotton mill use rose rapidly.

This led to the constant achievement of new records in domestic use for most of the 1980s, with consumption surpassing 20 million bales in many years, a trend that would only increase in the 2000s (to be seen in part two). Even with the new production records, China still needed to import cotton in about half of its years to supply its needs.

Xinjiang

The market liberalization period was also marked by notable geographic shifts, especially the expansion of cotton farming in Xinjiang, a remote northwestern region. While Xinjiang’s first state-run cotton farms were established in the 1950s, the region was considerably behind compared with those in the Yangzi heartland.

[Get a FREE Trial of our PREMIUM Cotton research today!]

The big expansion came in the 1990s as China sought to escape pest problems plaguing eastern cotton fields. Xinjiang’s arid climate had fewer cotton pests, and its large tracts of land were suitable for mechanized farming, which by then was far more widespread. This development would eventually lead to the dominance of Xinjiang as China’s top cotton-growing region, surpassing the established regions in Central China.

Conclusion

China possesses one of the oldest histories with cotton in the world. Although the Eastern nation always had the potential to become the world's biggest player, it took literally millennia to realize it.

In the first part of this blog, we covered the most important aspects of this journey, marked by wars, political and economic regime changes, and how those impacted the cotton sector. We also saw the developments of cotton production and consumption in its different aspects, such as absolute numbers, yields, and geography.

In the next part of this blog, we will follow China’s path as it pushes into the 20th century with a different mentality. We will explore the country’s full entry into international markets and the challenges faced in the last decades, as well as understand how the global cotton leader currently stands for the coming years.

Read Part 2 here: Cotton Origin Focus: China - Part 2

[Enjoyed this blog? Get more info from our PREMIUM cotton Market research. Try a FREE trial today!]

Comments