Cocoa Origin Focus: Ghana – Part 2

- Diego Miranda

- Dec 18, 2025

- 10 min read

Ghana Cocoa Sector At-a-Glance

• Production: 700k–800k tons per year. • Main Regions: Ashanti, Brong-Ahafo, Western North, Eastern. • Cocoa Type: Mostly Forastero. • Farm System: 800k+ smallholders, ~2–3 ha each. • Harvests: Main (Oct–Mar) and light (May–Aug). • Market: State-regulated by COCOBOD. • Pricing: Fixed farmgate price set by COCOBOD. • Economy: Cocoa is 2–3% of GDP, 20% of jobs, one-third of exports.

Introduction

In the first part of our cocoa Origin Focus: Ghana, we saw how this West African nation rose to the top of the cocoa world, only to lose everything it had fought so hard to achieve. We also saw the reasons behind Ghana’s decline, focusing on the effects of the State-controlled system, as well as the historical and political motives that led such a model to be adopted.

In the second part of this blog, though, we will explore how Ghana was able to change its ways, reforming the cocoa sector and assuming once again an important role in the global markets. That said, we will also investigate the limits of these reforms, seeing what has changed and what has remained the same.

From this point, we will be able to understand how Ghana came to where it is now and what we can expect of its future.

[Looking for reliable cocoa market research? Explore our Premium Cocoa Reports for timely insights and analysis.]

Reforms and Recovery (1980s–2000s)

The 1980s government reforms were foundational to Ghana’s current strength in cocoa production, setting the conditions to creating today’s powerhouse.

While Ivory Coast’s cocoa sector was booming, Ghana seemed to have stopped in time. Although the country had already seen eight different governments since its independence, three civilian and five military, there was little change regarding cocoa’s economic policies.

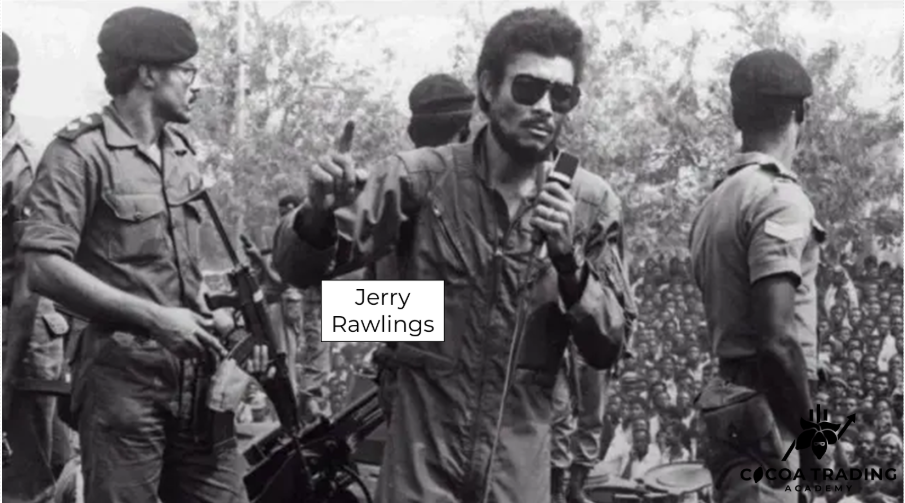

Facing the collapse of its signature crop, the Ghanaian government finally decided that changes were needed. The turnaround happened in 1983, under the government of Flight Lieutenant Jerry Rawlings, two years after he removed President Hilla Limann in a military coup.

The first and maybe most important step of the Rawlings program was to reduce the gap between farmgate prices and international markets. In 1984, as part of an economic recovery program, Ghana sharply raised the price paid to cocoa growers, reversing decades of heavy taxation. The previous differences were so large that the government increased the prices paid to farmers by over 10x in the first few years, and it still was not enough to match global cocoa prices.

Another early reform addressed corruption and inefficiency in cocoa purchasing. In 1982, the Akuafo Cheque System was introduced, replacing cash payments with guaranteed checks for farmers at the point of sale. This system eliminated the rampant practice of buyers defaulting on payments or cheating farmers with false weight claims. Now, a cocoa farmer in a village could sell beans to a licensed buyer and be handed a bank-guaranteed cheque – a seemingly simple step that greatly increased trust in the marketing system.

These changes were combined with massive investments in the rehabilitation of cocoa farms. Beginning in 1984, programs were launched to distribute free hybrid cocoa seedlings and cut down old, unproductive trees. Tens of millions of new seedlings were planted in the late 1980s to replace trees lost to disease and bushfires. The government and donor agencies also helped provide fertilizers, insecticides, and extension services to teach farmers better agronomic practices. New feeder roads were built into frontier farming areas that had rich soil but poor access, particularly the Western Region along the border with Ivory Coast, enabling farmers in those remote areas to get their cocoa to market more easily.

[Want deeper insight into the cocoa market? Our Premium Cocoa Reports break down the data that matters.]

Ghana also cautiously liberalized its internal markets. By the early 1990s, private Licensed Buying Companies (LBCs) were allowed to compete with the state purchasing company (Produce Buying Company) in buying cocoa from farmers, removing the government monopoly over this part of the sector. This partial liberalization created a hybrid system: dozens of private buyers entered local cocoa markets, offering farmers efficiency and convenience, although the state (COCOBOD) still maintained control over quality inspection and forward sales. The result was greater competition in services, which improved service quality and payment speed to farmers, but limited price competition due to COCOBOD's pricing caps.

Cocoa Reborn

Even though the reforms implemented by the Rawlings administration did not liberalize the markets completely, they were enough to produce drastic changes in the Ghanaian cocoa sector, with the first effects already notable in the 1980s. From the record low of 158,000 tons in 1983/84, Ghana’s cocoa output rebounded to about 227,000 tons by 1986/87 and then surpassed 400,000 tons in the 1990s.

After using the last decade of the twentieth century to recover, the Ghanaian cocoa sector soared in the 2000s. Not only did cocoa production match the previous record that had not been seen since 1964, but it went beyond it, surpassing 700,000 MT in four different years of the decade. Leaving its dark past behind, Ghana had firmly regained its position as a cocoa powerhouse – not the largest, but a strong second place globally.

At this point, Ghana and Ivory Coast together were producing well over 60 percent of the world’s cocoa, tightening West Africa’s grip on the market. The fact that both countries did not follow the usual market laws, instead setting official government prices and strictly regulating the selling process, made cocoa into a different crop from all other soft commodities, operating by its own set of rules and specifications.

Ghosts of the Past – Production Stagnates

Following the boom of the 2000s, Ghana reached 2010 in a strong position. Its yearly crop consistently surpassed 800 MT, something that could only have been called a dream a few decades earlier. That said, this was also the time when the sector’s structural problems gave their first signs of life.

Although Ghana’s crop was in an uptrend, its yields remained low. This means that most of its gains in production actually came from additional land and not from improvements in productivity. Not only that, but the yield growth that had started in the 1980s was interrupted in 2013, after surpassing 0.55 ton per hectare, leaving Ghana stuck as a low efficiency cocoa producer despite its importance as a global supplier.

Looking at the structural problems, it was easy to see that Ghana still had a long way to go. Although the 1980s reforms opened the cocoa markets substantially, their most important aspects were still controlled by the government. The COCOBOD remains the indirect buyer while also setting the farmgate price.

Under this arrangement, prices paid to cocoa farmers are significantly lower than the ones paid to farmers in countries that operate in a free market, such as those in South America. The system disincentivized production and methods for improving yields, instead leading farmers to seek ways to increase the price they receive, such as smuggling, which has been one of Ghana’s main challenges for decades.

[Access our Premium Cocoa Research for data driven market intelligence and analysis.]

The Production Crisis

Despite its problems, Ghana managed to sustain strong production in most of the last 15 years. Most seasons presented crops above 800 MMT and a new all-time high of 1047 MT was reached in 2020. Even the weaker seasons still presented figures close to 700 MT.

All that changed, though, in 2023, when the two main cocoa producers, Ivory Coast and Ghana, were hit by the strongest cocoa shortage in decades. The crops were damaged by terrible weather conditions compounded by the spread of different fungal diseases. Production, which already was in a downtrend, plummeted to just 500 MT, its lowest level in twenty years. The damage was so intense that it led cocoa to its biggest rally in history, surpassing $10,000 per MT for the first time in 2024.

Stuck in Their Ways

After the shortage, Ghana attempted to incentivize cocoa production by increasing the farmgate prices, which more than doubled in the last two years. Although a partial recovery was possible, with the 2024/25 crop surpassing 600 MT, it was still considerably below the usual levels prior to the shortage. A similar scenario is expected for 2025/26, as most of the market estimates a crop between 620 and 650 MT.

The 2023/24 crisis acted as a catalyst, revealing many of the problems that had been hidden in the Ghanaian cocoa sector. The main one, as we discussed, is the current market structure. Although Ghana took many steps to liberalize the sector, it is still tightly regulated by the government, which acts as the ultimate buyer and sets low prices for farmers to increase its own revenue. This system leads farmers to receive far lower margins than most of their competitors in other countries, disincentivizing production and increasing smuggling.

Beyond that, land that could be used for cocoa production is instead diverted to more profitable, even if prohibited, operations. The main example is illegal gold mining, which offers far higher profits than cocoa in Ghana, allowing mining companies to easily outbid farmers for land or even buy their cocoa farms, which are then destroyed so the land can be mined.

Instead of updating its market system, though, Ghana remains steadfast in the current model, attempting to deal with the challenges in a way that keeps the government’s role as the cocoa protagonist. One such example was the introduction of the Living Income Differential (LID), a fixed premium of US 400 per metric ton added to the market price for all cocoa sold by Ghana and Ivory Coast, aiming to lift farmers’ income. Although the LID’s goal was to improve farmers’ conditions, it attempted to do so in a way that placed all the burden on cocoa buyers, hoping that the Ivory Coast Ghana market dominance was enough to support it.

Despite the two countries representing over 65 percent of global cocoa production, it was still not enough to allow them to freely manipulate prices. Instead, what happened was a reduction of Ivory Coast and Ghana Country Differentials, the premium paid to cocoa from origins considered higher quality or more reliable. The Differentials, which had always been positive for both countries, turned negative for the first time, consuming most of the gains produced by the LID.

Market forces frustrated Ghana’s attempt to increase farmers’ income while keeping control of the cocoa sector for itself. For the government, maintaining control over the cocoa sector is fiscally critical, since it uses it as collateral for the annual syndicated loan, an important source of foreign currency that supports reserves, helps stabilize the cedi, and eases external financing pressures. At the same time, COCOBOD uses export margins to fund programs that would otherwise fall on the central government budget.

[Track cocoa markets with confidence using our Premium Research and ongoing analysis.]

As a result, from a political standpoint, it is easy to explain why the government does not wish to reduce its control of the cocoa market, which would also eliminate a considerable source of revenue. By keeping its current structure, though, it contributes to cutting farmers’ cocoa profits, which in turn disincentivizes production, increases smuggling, and accelerates the destruction of cocoa crops for gold mining, damaging the government’s own source of income.

Farming Challenges

Besides the market structure problems, Ghana also faces challenges regarding cocoa farming itself. Farms in the country are considerably behind in the most modern techniques, such as adequate pruning, fertilizing, sun exposure control, and irrigation.

At the same time, Ghana suffers from the aging of its cocoa trees. A cocoa tree’s optimal production happens when it is between 10 and 15 years old, after which its yields decline considerably. Ideally, trees should be replaced when they surpass 20 years, or 25 at most. In Ghana, though, it is common for farmers to keep their trees far longer than this, with some surpassing 40 years, meaning they were planted when the first reforms in the cocoa sector were introduced back in the 1980s.

Combined with rising fungal diseases, these factors led Ghana’s cocoa productivity to stagnate. Despite its role as one of the biggest global producers, Ghanaian yields are considerably lower than those of more efficient producers, such as Ecuador.

As it was 80 years ago, the rest of the world did not sit idle. The record prices caused by the 2023/24 shortage led dozens of nations to reevaluate cocoa’s potential as a source of revenue. One of them was Ecuador, one of the countries from which cocoa originated 10 million years ago.

Despite its role as the cocoa cradle, along with Peru and Colombia, Ecuador remained only a mid-size producer, harvesting less than 100 MT yearly. This began to change in the 2010s, as the country saw a boost in production, eventually surpassing 300 MT. Recently, though, the West African cocoa shortage gave Ecuador the boost it needed to truly take off; the South American producer was able to harvest almost 600 MT last season and is expected to surpass this threshold in the current one.

After decades of dominance, Ghana now finds itself in a tough spot. Considering most forecasts place Ghana’s 2025/26 crop around 650 MT, it is already possible that Ecuador will take its position as the second largest world producer this year. Even if it does not happen now, the current trend suggests it is only a matter of time.

Unlike Ghana, Ecuador’s cocoa sector operates in a free market system, in which producers negotiate directly with buyers and exporters, setting their own prices and keeping most of the profits for themselves. At the same time, its farming techniques are far more developed, using more advanced technologies and practices, which results in higher yields.

Conclusion

After decades of misery, Ghana was able to reform its cocoa sector, abandoning the worst of its practices and reclaiming its place as an important player in the global markets. That said, the West African nation failed to completely free itself from its former model, reforming it only enough to become more competitive while keeping the State as the main player and most benefited participant in the cocoa industry.

Now, its inability to fully let go of the past returns to haunt Ghana once again. As the country is hit by one of its worst cocoa crises in history, sharks all across the globe smell blood in the water and have started positioning themselves to take advantage of the situation.

If Ghana wishes to keep its position as the second biggest cocoa producer, it will need to reinvent itself once more. This time, though, it does not seem like a half done reform will be enough. Instead, a complete cocoa revolution might be the only way for it to outperform the newcomers.

So far, though, Ghana has not given any sign that it wishes to change its ways, choosing to increase the farmgate prices while keeping the current system unaltered. Whether it will sense the change in the winds and adapt accordingly, or remain bound to the past as other countries surpass it, only time will tell.

[Our Premium Research provides consistent, data-driven market intelligence.]

Comments